No Silver Bullet: Fighting Russian Disinformation Requires Multiple Actions

by Terry L. Thompson

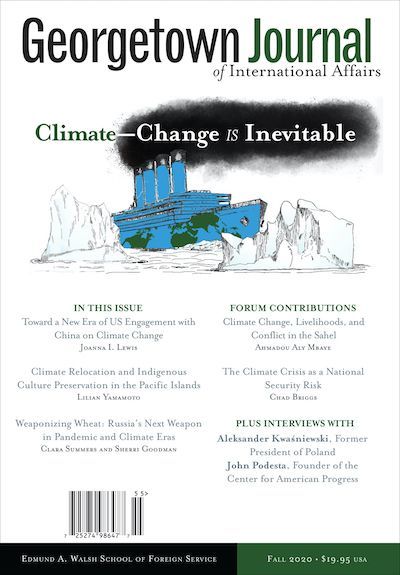

Georgetown Journal of International Affairs

Fall 2020 (Volume 21)

Terry L. Thompson is a lecturer in cyber policy at the Johns Hopkins University and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He transitioned to teaching after a forty-five-year professional career that included thirty years with the federal government and fifteen years at Booz Allen Hamilton, where he engaged in cybersecurity policy development for governments in the United States and six other countries.

Terry Thompson also discussed his recent article in a recorded GJIA YouTube Q&A session. During this recorded session, Thompson outlines how existing measures to combat Russian disinformation, especially in light of the US's 2020 presidential election, have been ineffective, and lays out what needs to be done to bolster the defenses of the United States and EU against information warfare.

You can also check out the full Fall 2020 Issue via Project Muse.

Purchase the CURRENT Issue of the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

Please begin reading the featured article below. Click the GJIA cover link to view the full article PDF.

With the November 2020 elections fast approaching, there is continuing concern about the effect of foreign interference affecting the voting process or outcomes of the election. For good reason. On October 21, 2019, in what could be an early indication of such interference, Facebook announced that it had taken down fifty Facebook and Instagram accounts that were associated with foreign entities. Although many posts were designed to build trust with like-minded social media participants, some focused directly on supporting the reelection of Donald Trump and disparaging Democratic candidates other than Bernie Sanders.1 While these tactics are almost identical to those used in the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) disinformation campaign in 2016, the IRA continues to evolve, using new methods including recruiting American citizens to post its disinformation in social media.2 In March 2020, US intelligence officials described Russian efforts to aggravate racial tensions by promoting white supremacist groups in private Facebook groups and anonymous message boards. These officials believe Russia is trying to create chaos in advance of the elections, giving President

Trump the opportunity to promise stability as the law-and-order candidate. Or, in the words of a senior FBI official, "To put it simply, in this space, Russia wants to watch us tear ourselves apart."3

Like the United States, the European Union (EU) has experienced Russian disinformation in social media during elections, most recently in connection with the 2019 European Parliament elections and the 2017 French and German presidential elections.4 More broadly, the EU and especially Baltic countries have felt the impact of Russian gaslighting, propaganda, and disinformation for decades, throughout the Soviet period and continuing in the post-Soviet era.5

The United States and EU have responded to these attacks on democracy by expanding monitoring efforts in social media and elsewhere, sharing threat information, and introducing regulatory measures. Europe developed an "Action Plan Against Disinformation" and a "Code of Practice on Disinformation," the latter a self-regulatory measure to encourage Facebook, Google, and Twitter to take responsibility for their platforms' content.6 Some countries have introduced laws to disable local access to disinformation in social media.7 The United States has taken a more operational approach, [End Page 182] exemplified by US Cyber Command's blocking of IRA operatives in the 2018 midterm elections.8 Outing Russian efforts in these ways has been only partially effective, however, and has not stopped their disinformation activities. The overall US effort to counter Russian influence operations has been inadequate. Without effective responses in multiple areas, Russia's efforts will not be deterred.9

The Fight against Disinformation

Many reports have described Russian cyber efforts to impact the 2016 election. The Intelligence Community Assessment of January 2017 summarized Russia's plan as one to "undermine public faith in the democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency. We further assess that Putin and the Russian Government developed a clear preference for President-elect Donald Trump."10 This report was bolstered by the comprehensive investigation of Special Counsel Robert Mueller and Congressional investigations in 2017 and 2018. Mueller's detailed report, together with the Department of Justice indictments it spawned, spelled out the tactics, techniques, and procedures used by the IRA in its attempt to interfere with the 2016 election.11

Despite continuing denials about the impact of Russian disinformation, including by President Trump himself, several studies assert that it did have an impact on the electorate, particularly on late deciders.12 With a polarized electorate and controversial incumbent, nothing suggests that 2020 will be any different, particularly given the fact that many Americans still reject the idea that Russia interfered in 2016.13

The US government, despite Trump administration denials, has applied lessons learned from 2016 to develop a comprehensive approach to deal with election interference. The Cyber and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), established within the Department of Homeland Security by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection Act of 2018, launched several initiatives to help state and local election officials across the country identify and address election vulnerabilities. CISA established the Elections Interference Information Sharing and... (click on journal cover image below to view the full article.)