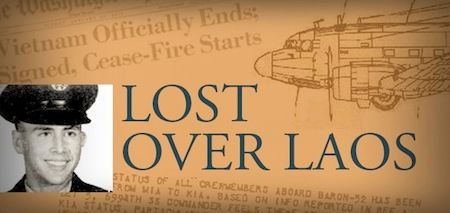

Vietnam War airman's death re-examined after decades of controversy

By Travis J. Tritten

Stars and Stripes

View the full story online at Stripes.com

Published: April 11, 2016

WASHINGTON — The Air Force closed the case on Sgt. Joseph Matejov when his surveillance aircraft went down at the end of the Vietnam War.

The missing airman was deemed killed in the fiery crash, and more than two decades later a group gravestone was installed at Arlington National Cemetery. A single casket containing bone fragments recovered in Laos was lowered into the ground at the 1996 funeral for Matejov and seven fellow Air Force crewmembers.

Officially, it was the end of the military’s accounting.

But the funeral did not bury the controversy over the downed aircraft, call sign Baron 52. The case’s long history is riddled with doubts and disagreements within the Pentagon, intelligence community and Congress over whether Matejov died that night in 1973.

Now, the Air Force and the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency are re-examining the incident after decades of pressure from Matejov’s family and could change his status from killed to missing in action. A decision could be made within weeks.

The airmen’s nine siblings, who have pushed for the change, in February presented evidence to the accounting agency of Air Force conjecture over the crash circumstances and a radio intercept about potential American captives. The evidence, spanning 43 years and compiled by the family, contains declassified documents and was shared with Stars and Stripes.

“MIA is not closure, though it is better than this travesty that exists in the file to this day,” said his younger brother John Matejov, who is a retired Marine officer. “We shouldn’t have to fight for that.”

The change would add Matejov to the list of 83,000 service members still missing and require DPAA to embark on a new effort to account for his remains.

An MIA status would be a stunning reversal for the Air Force, which has insisted since 1973 that there is no proof airmen escaped the Baron 52 crash. It would also be an extraordinary precedent for the DPAA to support the move, giving hope to other families still searching for loved ones lost in the war.

‘That KIA determination was wrong’

For Matejov’s family, the decades of uncertainty and frustration began with a letter from his wing commander a week after his EC-47 aircraft crashed.

“After careful consideration, I feel that there is a possibility that one or more crew members could have parachuted to safety, therefore your son will continue to be carried in a missing status until a final determination can be made,” Col. Francis Humphreys wrote to Matejov’s father and mother on Feb. 13, 1973.

Their hope was smashed days later by another letter from the colonel.

With little new evidence, Humphreys, who retired as a brigadier general and died in 2013, reversed his opinion and listed Matejov and all seven other crewmembers as killed in action.

“My chief concern is that KIA determination was wrong,” said Roger Shields, who was chairman of the Defense Department POW/MIA task group and directed the return of American prisoners of war during Operation Homecoming. “Nobody at the time when this decision was made could have said without any question that these men were dead.”

During the Vietnam War, the military often classified troops as missing in action – and assumed further effort might bring them back alive – even when the facts indicated otherwise, he said. Troops were rated MIA even when witnesses saw their aircraft go down with an intact canopy and no rescue beacon was activated.

“We just saw too many cases where it looked like the chances of survival were not that good but it turned out that people did survive,” he said.

LAST CONTACT

Joe Matejov turned 21 in February 1973. He had been deployed 10 months as an electronic warfare specialist with the Air Force Security Service, first to Vietnam and then to an airfield in Thailand. The classified work consisted of eavesdropping on North Vietnamese forces during flights over the officially neutral country of Laos.

His tour was wrapping up – 100 missions under his belt and a Distinguished Flying Cross in the pipeline – and he was ready to get back to the United States.

His EC-47 flew out of Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base just before midnight Feb. 4. The converted cargo plane, equipped with secret surveillance equipment, carried three other electronic warfare specialists from the 6994th Security Squadron and a four-man flight crew with the 361st Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron.

Over Laos, the flight left U.S. radar coverage. The airmen flew at a lofty 10,000 feet as they sniffed out North Vietnamese tanks moving south along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Crews had recently begun flying at the higher altitude to avoid artillery fire. Even so, parachutes were packed and each crewmember carried a survival radio preset to an emergency frequency.

Every 20 minutes, Baron 52 radioed Moonbeam, the airborne command-and-control center also plying the night sky over Laos. At 1:25 a.m., the crew reported 37 mm or 57 mm anti-aircraft fire but no damage.

There were no more updates from Baron 52.

Report: No evidence of survivors

Four days after the last radio contact, an HH-3E Jolly Green Giant helicopter hovered over the Baron 52 wreckage as it lowered two pararescuemen and a radioman. The airmen worked quickly once on the ground. The area was hostile, and approaching aircraft heard gunfire and were targeted by a missile. Two large North Vietnamese bases were just miles away.

“When we got there one of the PJs set up a perimeter, and the other one and myself were looking for bodies,” the technical sergeant radio operator at the time, Ron Schofield, said in a declassified Air Force oral history interview in 1989.

Schofield and the team searched for crewmembers and ensured the classified surveillance equipment used by the Air Force Security Service was destroyed.

The EC-47 was on its back. The rear of the fuselage – where Matejov and three other electronic warfare specialists were seated – was badly damaged after a heavy load of fuel burned off in the crash.

Still, the bodies of four airmen, including the seated pilot and copilot, were visible, preserved by their fire-retardant flight suits. The team was only able to recover the remains of pilot 1st Lt. Robert E. Bernhardt during a rushed 15 minutes on the ground.

Matejov and the other three “backenders” could not be seen in the wreckage.

“There should have been some remains of the backenders in the fire, but there wasn’t anything,” Schofield said in 1989.

The search-and-rescue report found no evidence of survivors. However, Schofield remembered a clue in the burnt fuselage that pointed to crewmembers escaping through a rear door.

“These aircraft flew with the doors on. If that aircraft had crashed with the door on, there would have been a little bit of it left at the top” where the plane had burned, he said. “It was gone. It looked like it had been kicked off.”

‘A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF CONJECTURE’

After the search, Humphreys believed some of the crew could have gotten out of the EC-47 before it crashed Feb. 5 on the jungle floor.

But pressure was mounting from the families over the missing-in-action status. They wanted progress in finding the airmen......" READ THE FULL STORY via STRIPES.COM

Return to our HOME PAGE.

Visit the Cryptologic Bytes Archives page via the "Return to List" link below.