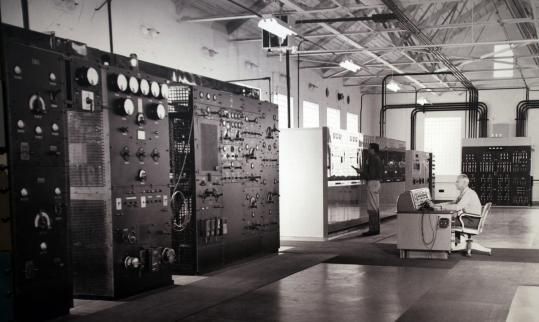

Photo: A file photo shows the interior of the converted World War II wireless receiving station in Chatham. (Steve Haines for The Boston Globe)

Chatham Station Played Pivotal WWII Role

Secret listening post collected U-boat messages to be decoded

By Laura J. Nelson

Globe Correspondent / June 28, 2011

CHATHAM — During World War II, as London burned and German submarines circled like sharks off the Atlantic Coast, the US Navy plotted a secret attack against the Nazis.

Tweet Be the first to Tweet this!

ShareThis

In a nondescript red-brick building in this sleepy Cape Cod town, the Navy converted a wireless radio receiving station into an intelligence hub that intercepted coded messages from German submarines and transmitted them to Washington, D.C., to be analyzed. The initiative, which ran from 1942 until the end of the war, employed nearly 600 sailors. But what went on inside the station was so secret that the naval archives has almost no information on it, and many longtime Chatham residents are just hearing about it now.

A short documentary produced by Edward Fouhy, a local resident and journalist, is the first to detail the station’s role in locating and sinking German U-boats that torpedoed American supply ships and tankers as they carried fuel and supplies to embattled Britain.

The film is playing at the former listening post, which is now the Chatham Marconi Maritime Museum. The museum opens today for its second season.

“The more I heard, the more I was struck by these brave young people,’’ Fouhy said yesterday. “Working here was a hard job, with no glory at all.’’

From 1939-1945, during the Battle of the Atlantic, German U-boats sank 2,600 Allied merchant ships, killing more than 30,000 American merchant marines, according to the museum.

But after this station and others along the coast began intercepting messages from U-boats to Berlin command centers, the Allies sank more Nazi submarines and got more supplies to England, turning the tide of the war.

Nearly 600 Navy men and later women worked around the clock on two tasks: sending intercepted code to Washington to be translated through a captured German code machine called Enigma; and working with other stations on the East Coast to pinpoint U-boats.

Tuning to a certain radio frequency created an invisible line between sender and receiver, Fouhy said. When multiple stations listened to a German submarine’s transmissions, the intersection of those lines determined the U-boat’s position.

The number of submarines the Allies sank spiked, and the number of Allied vessels bringing supplies to Europe soared after Chatham began helping. Soon, the station was the busiest in the Western Hemisphere, said Charles Bartlett, the museum president.

Chatham’s job was made easier by Admiral Karl Dönitz, head of the U-boat program and later head of the German Navy, who became head of state after Hitler died. Fouhy called Dönitz a talkative control freak who insisted that his submarines surface each night for the next day’s orders.

“Even after the Americans and the British cracked his code, he refused to believe it,’’ Fouhy said. “And he really liked to talk.’’

Fouhy said he found no record of the station at the Naval Intelligence office in Washington, and no footage or photos in the naval archives in Baltimore. So he used Universal newsreels, photos from private archives, and information from wartime memoirs, including Winston Churchill’s.

Those who worked at Chatham took a vow of silence that held long after World War II ended, said museum spokesman Peter Cocolis. Now, there are few veterans left who served there.

Bartlett said he began coming to Chatham during World War II while his father was fighting overseas. He does not remember meeting any station workers.

“I don’t think any of us knew what they did, only that they were there,’’ Bartlett said. “And most of us just said, ‘Well, it’s not my business.’ ’’

Many photographs in the video came from Dick Lumpkin, a naval officer from Baltimore who became the station’s chief.

After Lumpkin’s death in 2008, his daughter, Donna Lumpkin, began sorting through an archive he left about the station, including photographs and rosters, Bartlett said.

In the attic of the Chatham building, filing cabinets, boxes of wireless equipment, and original blackout shades clutter the same floors and alcoves where German coded messages once came in.

The station’s role in World War II is not its only claim to fame. When Guglielmo Marconi, a radio and wireless pioneer built it in 1914, he dreamed of a world communicating wirelessly.

Marconi was communicating with Scandinavia by the time RCA acquired the station in 1921.

For the next 73 years, Chatham was the predominant ship-to-shore wireless station.

Laura J. Nelson can be reached at lnelson@globe.com.

© Copyright 2011 Globe Newspaper Company.

Read the article online HERE.