By EMMA G. FITZSIMMONS for the New York Times

Published: December 24, 2013

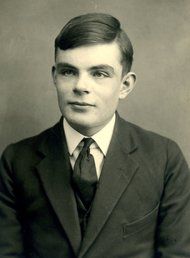

Nearly 60 years after his death, Alan Turing, the British mathematician regarded as one of the central figures in the development of the computer, received a formal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II on Monday for his conviction in 1952 on charges of homosexuality, at the time a criminal offense in Britain.

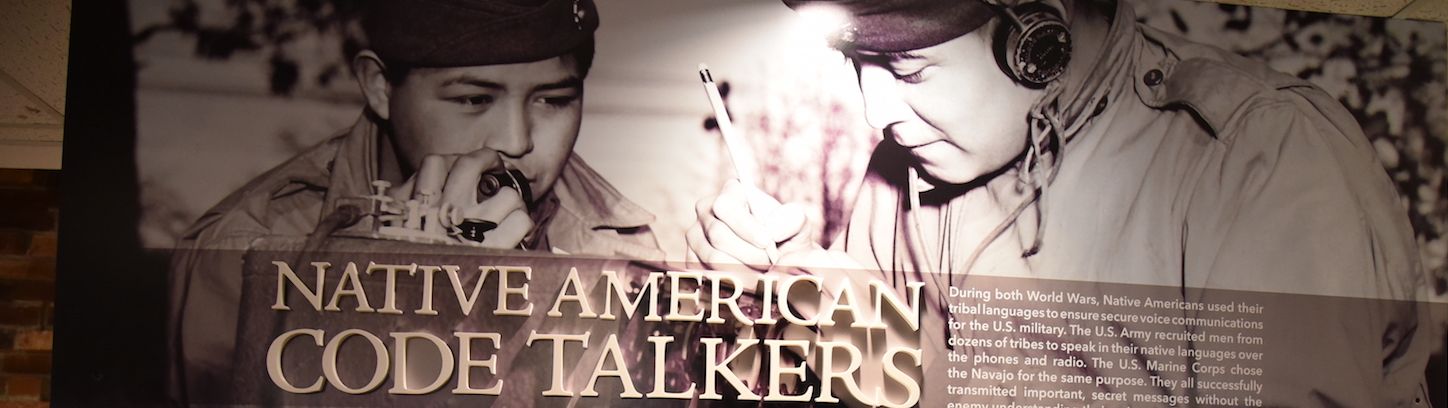

The pardon was announced by the British justice secretary, Chris Grayling, who had made the request to the queen. Mr. Grayling said in a statement that Mr. Turing, whose most remarkable achievement was helping to develop the machines and algorithms that unscrambled the supposedly impenetrable Enigma code used by the Germans in World War II, “deserves to be remembered and recognized for his fantastic contribution to the war effort and his legacy to science.”

The British prime minister, David Cameron, said in a statement: “His action saved countless lives. He also left a remarkable national legacy through his substantial scientific achievements, often being referred to as the ‘father of modern computing.’ ”

Mr. Turing committed suicide in 1954, two years after his conviction on charges of gross indecency. He was 41. In a 1936 research paper, Mr. Turing anticipated a computing machine that could perform different tasks by altering its software, rather than its hardware.

He also proposed the now famous Turing test, used to determine artificial intelligence. In the test, a person asks questions of both a computer and another human — neither of which they can see — to try to determine which is the computer and which is the fellow human. If the computer can fool the person, according to the Turing test, it is deemed intelligent.

In 2009, Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued a formal apology to Mr. Turing, calling his treatment “horrifying” and “utterly unfair.” But Mr. Cameron’s government denied him a pardon last year.

An online petition urging a pardon received more than 35,000 signatures. The campaign has also received worldwide support from scientists, including Stephen Hawking.

When Mr. Turing was convicted in 1952, he was sentenced — as an alternative to prison — to chemical castration by a series of injections of female hormones. He also lost his security clearance because of the conviction. He committed suicide by eating an apple believed to have been laced with cyanide.

The queen has the power to issue a “royal prerogative of mercy” to pardon civilians, but rarely does so. Mr. Grayling said that Mr. Turing’s sentence would today be considered “unjust and discriminatory.”

Mr. Turing has been the subject of numerous biographies, as well as “Breaking the Code,” a play based on his life that was presented in London’s West End and on Broadway in the 1980s.

Go to the original New York Times article.