The Adventures of Lightning Ellsworth

By STEPHEN E. TOWNE

DECEMBER 23, 2012

In December 1862, Gen. Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, was encamped around Murfreesboro, Tenn. Nearby, poised to attack him, was Union major general William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, headquartered just 35 miles away in Nashville.

Bragg planned to stop the Union advance by hitting their stretched supply lines. He first sent a cavalry brigade under Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest into west Tennessee to destroy federal supply lines, then feeding Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army advancing on Vicksburg, and thus securing his own western flank. More immediately, he ordered a powerful cavalry force under the newly promoted Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan to ride north into federally controlled Kentucky to destroy bridges on the Louisville & Nashville railroad, the vital supply line bringing food and ammunition to Rosecrans’s forces.

Morgan was the ideal commander for the risky task. A daring guerrilla cavalry commander from Kentucky, he had become a Southern hero for his bold raids into his home state to smash railroad lines, destroy federal supply bases and rally pro-rebel sentiment. His force, mostly fellow Kentuckians, knew the landscape thoroughly and yearned to break the federal occupation. Moreover, Morgan’s men were familiar with the L&N, having destroyed part of the rail line earlier that year. Bragg ordered Morgan to repeat the feat. Morgan and his 3,900-man force, a combination of cavalry and artillery, moved out from Alexandria, Tenn., on Dec. 22.

Morgan was a daring and efficient general, but a big part of his success as a guerrilla fighter came thanks to his telegraph operator, George A. Ellsworth. Ellsworth, born in Canada, was only 19 years old, but he already had years of experience in his trade. He possessed a slippery, chameleon-like personality that allowed him to blend into any crowd. In 1860 he had marched in torch-lit parades in Indiana with the paramilitary Wide Awakes, who supported Abraham Lincoln during the presidential campaign. In 1862, while working in Texas, he became wild for the Confederate cause and traveled east to join Morgan’s band in July.

Using a pocket instrument that he attached to telegraph wires, Ellsworth immediately demonstrated a quick-witted ability to intercept messages, mimic operators on the line, absorb information and tap out false messages to federal commanders. He frequently misled them about the whereabouts of Morgan’s forces, sending their powerful pursuers in the wrong direction and luring weaker forces within the raiders’ grasp.

Riding with Morgan’s staff, he often joined the advance scouts who rode ahead of the main column quickly to seize a telegraph office to prevent the operator from sending out alerts. There, he employed his skill as a mimic, imitating the cadences of the captured operator to send and receive messages. He matched Morgan’s style of warfare well: strike weak targets and avoid stronger foes, confuse with feints, exaggerate strength to overawe a more powerful enemy.

Southern newspapers published Ellsworth’s report to Morgan on his telegraphic activities during the July Kentucky raid to great acclaim. Reprinted in Northern papers, the report made Ellsworth a sensation for his devious use of wartime telegraphy. Even The Times of London remarked upon his “impudence” and “dexterity in the strategems of war.” Morgan’s men nicknamed him “Lightning.”

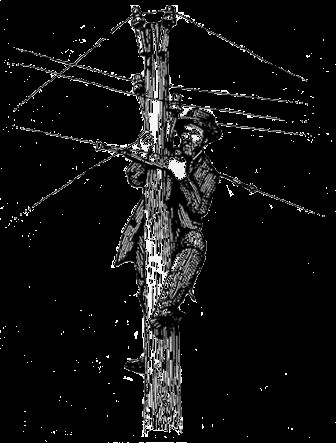

On the winter mission, often called the Christmas Raid, the now-notorious “Lightning” Ellsworth again rode northward into federally controlled Kentucky on Morgan’s staff. When encountering a telegraph line, troopers would shin up the poles and pull down the wire, to which Ellsworth would attach his pocket device. Years later, a fellow trooper recounted seeing Ellsworth at Upton Station on the wire, “seated on a cross-tie within a few feet of General Morgan,” who dictated misleading messages to his operator and enquired about “the disposition of the Union forces, and at the same time telling some awful stories” about where his own force was.

In his 1882 memoir, Ellsworth recounted that he spent the whole of Christmas Day listening to messages passing over the wire. He then caught up with Morgan miles ahead and reported that he learned the strength of the infantry force defending their main target: the long trestle bridges on the L&N near Elizabethtown, about 40 miles south of Louisville.

Federal commanders, alerted by their own spies to Bragg’s orders to send Morgan north, attempted to set traps for the Confederates. Well aware of Ellsworth’s deceptive skills, they warned one another to be wary of any telegraph messages they received. “The rebels have good operators, and Morgan may telegraph you direct,” wired one general.

Rosecrans planned a pincer movement to entrap the raiders. Some 10,000 troops guarded the L&N through Kentucky and Tennessee, many of them stationed in small log stockades along its route. Another 10,000 occupied other parts of Kentucky. Rosecrans diverted thousands of other troops from his planned attack on Bragg’s army in the effort to catch Morgan, telling them: “Don’t credit the big stories” that Morgan “sends abroad, but tell your men to fight them.”

For all of the Union Army’s efforts to trap the rebel raiders, Morgan succeeded in evading them. Riding in daytime and through dark nights in freezing winds and sometimes soaking rain, the raiders destroyed bridges, depots and other infrastructure and overwhelmed small guard detachments strung along the railroad. Morgan reached Elizabethtown on Dec. 27, and after a sharp bombardment forced the surrender of a regiment of Illinois infantry.

He then headed for the great trestle bridges — 70 feet high and over 300 feet long — a few miles north of town and compelled the surrender of the Indiana troops guarding them. The next day Morgan’s men systematically destroyed the trestles, lighting the wooden structures in a “most magnificent bonfire.” They destroyed miles of track by heating the rails and bending them around trees. They also ripped down miles of telegraph lines.

The attack was a complete success and, given the obstacles, relatively easy. But the return trip, by a different route, was more hazardous. Dogged by pursuing forces, Morgan’s men skirted a large federal force at Lebanon in the night, aided by Ellsworth continued telegraphic deceptions. On New Year’s Day the riders could hear the distant thunder of heavy artillery fire — Rosecrans and Bragg had joined battle on Stones River, back in Tennessee. The next day the raiders slipped across the Cumberland River in Tennessee to safety. Their 500-mile raid was a success. But they failed to stop Rosecrans’s attack.

After his defeat at Stones River, Bragg retreated southward. With their regular supply line destroyed, Rosecrans’s army, reduced to half-rations, subsisted on supplies sent up the Cumberland River on steamboats heavily guarded by Union Navy gunboats and could not immediately press forward. Herculean efforts repaired the L&N bridges, and by February 1863 trains again resumed supplying Rosecrans’s army, now camped at Murfreesboro.

Ellsworth continued to serve Morgan until the general was captured in Ohio on another raid in July 1863. Ellsworth escaped and served the Confederacy on missions behind federal lines to tap telegraph wires and listen in to military communications. Captured in 1864 in eastern Kentucky while on a secret mission, he escaped to Canada, where he joined the Confederate secret agent Capt. Thomas Henry Hines in failed efforts, in collaboration with Northern conspirators, to release Confederate prisoners-of-war at Camp Douglas near Chicago. After the war, Ellsworth murdered a Kentucky man, escaped jail, attempted to rob trains in Texas and died in 1899 in Louisiana — working, again, as a telegrapher.

A thoroughly bad character, Ellsworth nevertheless prompted widespread imitation. In 1863 General Rosecrans, an aggressive intelligence gatherer, sent volunteer telegraphers into rebel-controlled eastern Tennessee to tap Confederate lines. By war’s end, both sides had intelligence operations that routinely tapped one another’s wires to steal information and send out deceptive messages. If war was hell, it was also ungentlemanly.

Sources: Stephen E. Towne and Jay G. Heiser, eds., “‘Everything Is Fair in War:’ The Civil War Memoir of George A. “Lightning” Ellsworth, John Hunt Morgan’s Telegraph Operator,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 108 (Winter/Spring, 2010); John Allen Wyeth, “With Sabre and Scalpel: The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon”; Basil W. Duke, “History of Morgan’s Cavalry”; India W.P. Logan, ed., “Kelion Franklin Peddicord of Quirk’s Scouts, Morgan’s Kentucky Cavalry, C.S.A.”; William R. Plum, “The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States”; James A. Ramage, “Rebel Raider: The Life of John Hunt Morgan”; Edwin C. Bearss, “General John Hunt Morgan’s Second Kentucky Raid, December, 1862,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 70-72 (1972-74).

Stephen E. Towne is an associate university archivist at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and the editor of “A Fierce, Wild Joy: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Edward J. Wood, 48th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment.”

Read the New York Times article online.