In an article for the New York Times by John Markoff on July 25, 2011 (below), he discusses a Library of Congress finding by Steven Bellovin of a codebook that describes a technique called the one time pad. The codebook was published a full 35 years before its supposed invention during World War I by Gilbert Vernan.

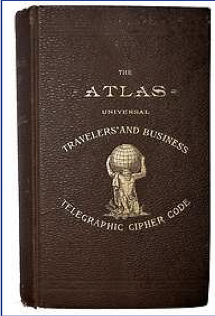

Photo by Steven Bellovin (KEY Codebooks like this one (pictured above) from 1896 cut the cost of telegrams, which were charged by the word.)

Codebook Shows an Encryption Form Dates Back to Telegraphs

By JOHN MARKOFF

Published: July 25, 2011

NY Times - Full Article

If not for a computer scientist’s hobby of collecting old telegraph codebooks, a crucial chapter in modern cryptography might have been lost to history.

The collector is Steven M. Bellovin, a professor of computer science at the Columbia University School of Engineering and a former computer security researcher at AT&T Bell Laboratories. On a recent trip to Washington he found himself with a free afternoon and decided to spend it at the Library of Congress, looking for codebooks that weren’t in his collection.

In the 19th century codebooks were used not so much for secrecy as for compression, to bring down the prohibitive cost of telegraph communication. (The first trans-Atlantic cables cost $5 a word.) Designers devised lists of words to replace phrases and even sentences.

But when Dr. Bellovin hunted though the card catalog, his interest was piqued by an 1882 codebook whose title included the word “secrecy.”

“I thought, ‘O.K., let me go see how they did it,’ ” he recalled. “When I read the two-page preface, my jaw dropped.”

He could plainly see that the document described a technique called the one-time pad fully 35 years before its supposed invention during World War I by Gilbert Vernam, an AT&T engineer, and Joseph Mauborgne, later chief of the Army Signal Corps.

Although not widely used today because it is relatively difficult to work with, the one-time pad is still viewed as one of strongest ways to encrypt a communication. The technique is distinguished by the use of a random key, shared by both parties, to encode the message and decode it; the key must be used only once and then securely disposed of.

It was the Soviet Union’s misuse of the technique — code clerks were occasionally reusing the one-time pads instead of discarding them — that led to the Venona project, the collaboration between the United States and British intelligence services that yielded code- cracking coups during World War II and the cold war.

The 1882 monograph that Dr. Bellovin stumbled across in the Library of Congress was “Telegraphic Code to Insure Privacy and Secrecy in the Transmission of Telegrams,” by Frank Miller, a successful banker in Sacramento who later became a trustee of Stanford University. In Miller’s preface, the key points jumped off the page: “A banker in the West should prepare a list of irregular numbers to be called ‘shift numbers,’ ” he wrote. “The difference between such numbers must not be regular. When a shift-number has been applied, or used, it must be erased from the list and not be used again.”

That sent the astonished Dr. Bellovin to the Internet to try to find out whether Mr. Miller’s innovation was known to the later inventors.

The results of his largely online detective work can be found in the July issue of the journal Cryptologia. Born in Milwaukee in 1842, Mr. Miller attended Yale and then joined the Union Army, where he fought at Antietam and was wounded at the Second Battle of Bull Run.