-

EDUCATE

EDUCATE...our citizens to be cyber smart, and develop pathways for the future cyber workforce.

-

ENGAGE

ENGAGE...and convene partners to address emerging cyber and cryptologic issues.

-

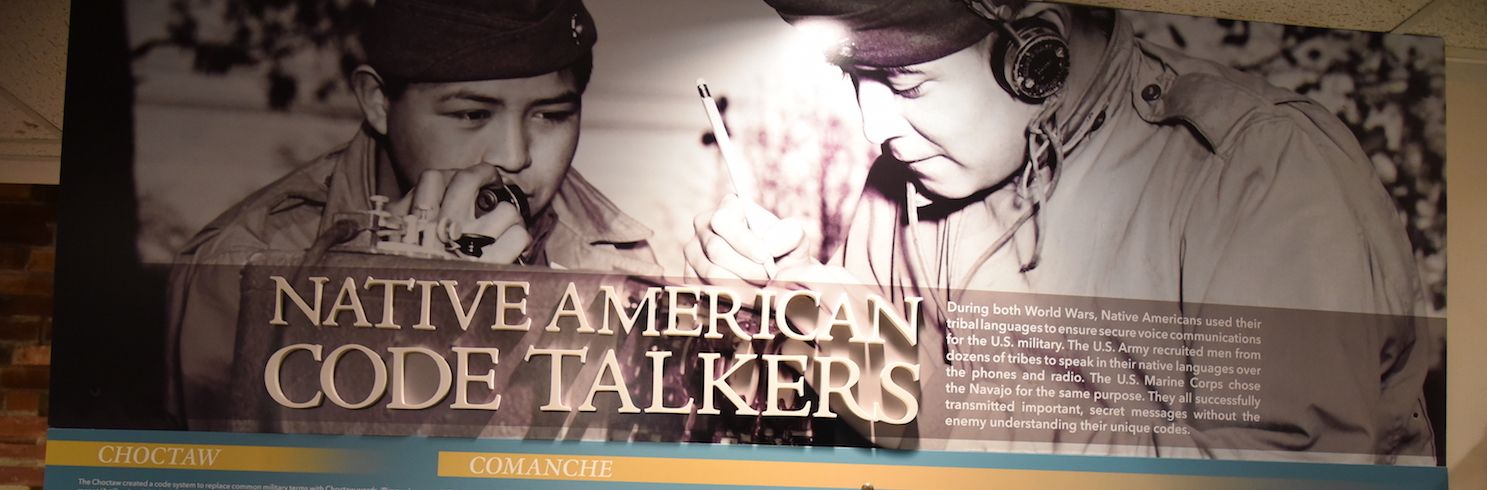

COMMEMORATE

COMMEMORATE...our cryptologic history & those who served within the cryptologic community.

The National Cryptologic Foundation is a private 501(c)(3) organization not affiliated with the U.S. Federal Government.

Return To List

Cryptologic & Cyber Dates in History

-

Birth of Philip Johnston, man behind the proposal to use the Navajo language as a code in WWII.